Co-op Member’s Latest Effort Zeroes in on City’s Democratic Machine

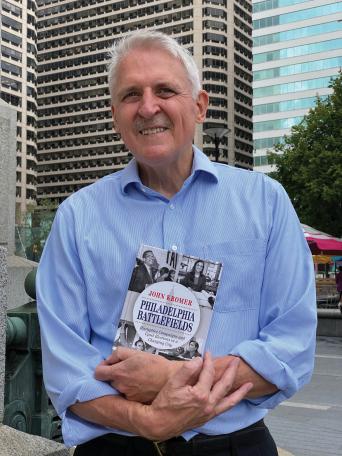

Weavers Way member John Kromer’s recently published book, “Philadelphia Battlefields: Disruptive Campaigns and Upset Elections in a Changing City,” unmasks the internecine Democratic party politics that subtly influence and govern our lives as Philadelphians.

Kromer takes us back to the 1951 election when Joseph Clark and Richardson Dilworth upset almost a century of Republican Party rule to become mayor and district attorney respectively, ushering in the new era of the Democratic Party machine.

The original architecture of Philadelphia’s Democratic City Committee, which exists largely to get out the vote for its endorsed candidates, lives with us today. It’s based on a political map that divides the city into 66 wards, each with their own ward leader who commands a dozen or more divisions; each of those has two elected committee people. Most residents are only dimly aware of this structure, even though they visit the tip of the iceberg twice a year — the polling place assigned to their division. If you have ever had someone try to press a preferred ballot ticket into your hand as you entered the polling place, then you have encountered the inner workings of the DCC and your local ward leader.

While Kromer argues that the ward system has the potential to embody the highest ideals of representative democracy, the domination of local politics by a single party over an extended period of time has not been without consequences. They include the weakening of civic structure, corruption and mismanagement, long-term incumbency, resistance to progressive reformers and, as we saw in the 2016 presidential election, reduced voter turnout.

At the heart of Kromer’s hopeful book, however, is an analysis of dozens of instances in which ambitious, strategic outsiders defeated the DCC to win elections at the most granular level of committee person and ward leader, as well as citywide and regional positions such as mayor, controller and congressperson. Presented through engaging stories based on first-person interviews, “Philadelphia Battlefields” reveals the varied strategies of a compelling roster of Philadelphia’s activists and elected leaders.

The book is a good resource for any Philadelphian who wants to understand our city better. But if you want to challenge the status quo — whether as an outsider working to influence policy and political leaders, or by aiming for public office — “Philadelphia Battlefields” is essential reading.